Rituals, customs and traditions of Setsubun

Make a spiritual trip and immerse into the Japanese culture by observing the practices of Setsubun Festival.

Basic elements and practices of Setsubun festival

Observing the rituals and customs of Setsubun is definitely a unique experience that reveals the long tradition and the spirituality of Japanese culture. Some of the rituals are taking place at home, while others are followed at shrines and temples. The nice food that is involved in the celebration as well as the entertaining and peculiar practices make Setsubun a highly anticipated festivity for the whole society. Today, the public events attract many locals and visitors and some of them are televised on a national level.

Being a traveler in Japan during the Setsubun festival gives an extraordinary opportunity to find out the folklore background and observe rites and habits that are identical parts of Japanese society. Even for those who are not privileged enough to have local friends or relatives, there are chances to get the festive spirit through a series of events or even purchased items that are available in shops and play a central role in the celebration. Some of the most significant highlights of the festival are:

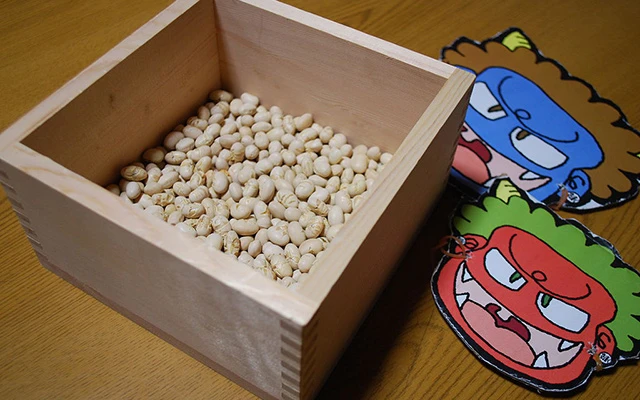

Bean throwing (mamemaki)

Mame-maki is the ritual that targets to chase away the evil spirit (oni) and keep a healthy environment in the house. It literally means bean-scattering but given that the word mame (bean) is homophone to another word meaning “destroying evil” the term mamemaki implicates the role of the practice itself.

Mamemaki is a family tradition, occurring at night when the whole family is at home. Then the oldest member, usually the father, wears a demon’s (oni) mask and pretends to enter the house. The rest start throwing roasted beans against him shouting “Oni wa soto!, Fuku wa Utsi!” (Demons out!, Good fortune in!). When they chase the demon out of the house they slam the door shut. The soybeans should be roasted and at the end, all should be gathered from the floor since it is considered unlucky if a bean is forgotten and leave sprouts.

Eating roasted beans (daizu)

According to the tradition after the mamemaki ritual and when the oni leaves the house, each member of the family has to eat a number of beans (plus one) that corresponds to his/her age. This promises good health for the upcoming year.

Soybeans (daizu-the big beans) are considered as one of the most powerful crops in Japanese culture and according to the common belief, they are very effective against oni demons. This because according to a theory, the word mame (bean) is a combination of the words ma (devil) and messuru (perish / disappear). During Satsubun they are sold in small bags called fuku mame (fortune beans) and for the mamemaki ritual, they are collected to wooden sake boxes called asakemasu.

Shrines and temples

Apart from the “home/family oriented version”, the bean throwing ceremony (mamemaki) can be observed in one of the numerous public events that are held in Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines across the country. Those are admission-free rituals that attract hundreds of locals and tourists.

Usually, the guest-stars of those ceremonies are celebrities, famous sumo wrestlers and other personalities. There, the observer has the opportunity to attend the mamemaki ritual and receive one of the lucky soybean-packets which are thrown to the crowd.

The evil spirits (oni)

The oni are the representation of the evil spirits and they have a central role at the ritual of “bean throwing” (mamemaki). They are featured in many aspects of the Japanese culture and people become aware of them at an early age through numerous children stories.

They resemble trolls and ogres and with the use of costumes and masks, they are depicted as scary and evil creatures. The oni are either red or blue, having sharp teeth and claws, long wild hair and two horns.

Given that it is the father’s duty to dress up like oni, in most of the cases, children recognize him and enjoy the process of chasing the “bad demon” but sometimes depending on the success of disguise, the whole concept can provoke real fear to the young “ghost-busters”!

Holly sprig and sardine (hiiragi iwashi)

According to common belief, the oni (evil spirits) do not like smelly fish and they are afraid of the sharp leaves of holly sprig which can point out their eyeballs.

During an old custom, people were burning dried sardine heads in ceremonies accompanied by the noise of drums. Today as a remnant of this tradition, some people decorate the entrance of their houses with baked sardine’s heads together with the holly sprig. This tradition, named hiiragi iwashi, draws its’ routes to the Heian period (a thousand years ago) and it is mainly followed at the regions of Kanto and Nara.

Some households keep those pieces on the door for the whole year, while others cast away them by following some special rituals. Either they burn them in a shrine or their throw them away after wrapping it in Japanese writing paper and purifying it with salt.

Sushi roll (ehomaki)

The main and most distinctive food of Setsubun is ehomaki. This is a special sushi roll made out of 7 ingredients that represent the seven deities of good fortune (shichifukujin).

Regardless of the type of ingredients, their number should be always the same (seven). They should be rolled tight in order to keep the elements of prosperity, good health, and happiness closed in.

Eating the ehomaki is a ritual on its’ own. Given that “eho” means “lucky direction”, it is crucial that the entire sushi roll should be eaten in the evening while the person should be turned to the “lucky direction” which is different for each year. Everyone should eat the ehomaki in silence, using both hands, and making a wish for good health and happiness for the upcoming spring as well as for the whole year. Moreover, someone has to eat ehomaki as a whole without cutting it, since slicing it symbolizes cutting the good fortune.

Nowadays, the ehomaki roll is sold almost in every supermarket and convenience store in Japan.